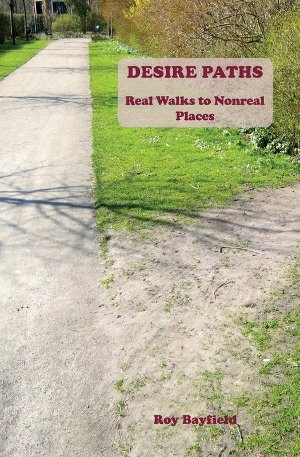

I read a book called Desire Paths by the psychogeographer and poet, Roy Bayfield, and I keep returning to the following passage:

If I was the most important element of the landscape, if everything revolved around me, then the growth of blanket weed in the canal, the fading paint on the narrowboats and the additions of graffiti on the underpass would have been measured to quantify my absence. The St. George flags on the new canalside apartments would be there to celebrate my slain dragon. But none of these things were the case so we were free to just walk and notice: meadows visible through the hedges; a heron, with a whole fish in its neck; features of rail and canal architecture collapsing into the natural environment; empty chairs at the back of a factory. (Bayfield 2016: 22)

I admire the way he combines magick, art and spirituality. The book is a nexus of all three. This passage shows how he achieves it: a delicious letting-go of any sensible, central I.

It is because none of us is at the centre that we really are free. Things are never more themselves when unmeasured in relation to us. Letting drop the urge to find ourselves in everything is a hallmark not just of psychological maturity, good poetry, and meditative practice, but also – evidently – of Bayfield’s unique flavour of psychogeography.

Accompanying him in his enchantments of meaning from space and place is a vicarious and intense magickal pleasure.